Bill: Ok, we both have the book, and we're ready to get started! Here is a brief video of me smelling my copy:

Allana: The book itself has six sections - five "iterations" and a "modus" at the end. Thus, I'm thinking a larger section summary every five days, along with the weekly chats and all the posts in between. We should probably plan a big blowout at the end, huh.

Bill: How about we do the section summaries on Mondays and Fridays, so the schedule is something like:

Section summary posts on these days:

Iteration 1: 4/5/2010

Iteration 2: 4/9/2010

Iteration 3: 4/12/2010

Iteration 4: 4/16/2010

Iteration 5: 4/19/2010

Modus: 4/23/2010

Weekly chat posts (like this one, but more interesting!) on Wednesdays:

Chat 1: 4/7/2010

Chat 2: 4/14/2010

Chat 3: 4/21/2010

Chat 4: 4/28/2010 (this one takes place after we've finished the book)

Anyone who might be reading along with us, that might serve as a framework for our team pacing through the book.

Any other posts fall around those whenever we have something. Allana: I'm glad I went through with those Known Issues things, unpleasant an exercise as they may have been. I've got the sort of feeling that comes after a long phone conversation with my well-intentioned-but-pushy Catholic aunt, when she thinks she's consoling me. First comes the list of the great dangers and worries the world has in store for me, all the things I shouldn't do, won't like, have to keep on guard for. Then there's the unavoidable conclusion - "But if you ask the Lord to guide you, there won't be any problems at all. He's just waiting to be asked."

Allana: I'm glad I went through with those Known Issues things, unpleasant an exercise as they may have been. I've got the sort of feeling that comes after a long phone conversation with my well-intentioned-but-pushy Catholic aunt, when she thinks she's consoling me. First comes the list of the great dangers and worries the world has in store for me, all the things I shouldn't do, won't like, have to keep on guard for. Then there's the unavoidable conclusion - "But if you ask the Lord to guide you, there won't be any problems at all. He's just waiting to be asked."

Finally, I'm ready to do all the things I've been warned against.

Bill: For my part, I'm just excited to be reading a science fiction novel of substance alongside someone else. I'm not one generally for book clubs (though I did run a physics based one for a time) as they tend to gravitate toward books I'm just not interested in. But reading in a conversational vacuum can get old. The Whitechapel book threads are cool up to a point, but people rarely engage around a particular book for more than a post or two. I haven't done much real concentrated reading with peers since graduating college, and it was something I really enjoyed.

The Pre-Game.

Written by Allana on Saturday, April 03, 2010

The Angel of Goliad.

Okay, so, I didn't start reading early - I swear, Bill! - but I did peek inside the book while waiting for the all-clear signal. The title of the first "iteration" of The Difference Engine is "The Angel of Goliad." What's Goliad, you ask? Okay, that's what I asked. Anyways. It's a town in Texas. The only thing it seems to have going for it is a pretty sad-looking massacre in 1836. (No, really.)

Now, being Canadian and thus oblivious to all those dirty little political skirmishes my neighbours down south still hold grudges over, I didn't actually know that Mexico tried to invade Texas. It's not exactly something you'd expect -- what's so interesting about Texas? (Other than that every single town claims to be a different "capital of the world" - cowboy, live music, pecan? Leap Year?! Killer Bee! I guess it's not the worst marketing strategy I've ever seen. But it is pretty atrocious.)

Trust the Mexicans not to be killin' Yankees for the sake of killin' Yankees. Goliad is where the first declaration of independence for the Republic of Texas was signed - the Americans had actually captured it from the Mexicans a year earlier than the Massacre, and held it up until that point. In March of '36, the Mexicans reclaimed it and did a rather ungentlemanly thing: they declared all the surrendered prisoners "pirates" and slaughtered them. Not cool, Mexico.

Then there was a bit of back-and-forthing until the Texan army won the Battle of San Jacinto and drove the Mexicans back. Thus was the Lone Star State - err, Republic -- born.

So the Angel of Goliad is.... a woman named Francisca Alvarez. She was the wife of a Mexican officer and traveled with his army, but tended wounded soldiers on both sides of the battles she saw. She earned her moniker by freeing ten Texan soldiers who were to be shot after Goliad was surrendered. In typical flowery prose, one of the men she rescued wrote of her:

Her name deserves to be recorded in letters of gold among the angels who have from time to time been commissioned by an overruling and beneficient power to relieve the sorrow and cheer the hearts Of men; and who have, for that purpose, been given the form of helpless women. (Source.)What a charmer.

Anyways, that's today's history lesson. What London in 1850 has to do with a mysterious Mexican flower-woman is anyone's guess.

- Allana

Written by Allana on Friday, April 02, 2010

Known Issues, part three.

I know, right: Why put myself through the torture of a third part when I just about had my faith in humanity crushed in the second? Answer: change of tactics. Let's see if we can't identify some of the nice things positive reviewers are saying that might be worth taking issue with.

(Vendetta against the entire world? What vendetta against the entire world?)

As evidenced by the existence of The Difference Dictionary, there are more than enough references to factual figures to keep the plot from taking too many artistic liberties:

There's something here for everyone as famous scientists, politicians and artists all make appearances - only the most erudite reader could catch them all, but every one you do catch gives a tiny frisson of being in on the joke. It's a brilliant combination of historical research and creative re-imaging pulled off with considerable style. (Source.)This sort of name-dropping does indeed impart a sense of elitism to the reader. I'm just starting Jonathan Lethem's Chronic City, and the main character's new best friend spends most of the first chapter playing up obscure films. It takes place in the Criterion offices, as a matter of fact, and I Am Curious (Yellow) gets mention on the second page. I can't imagine anyone without a fine arts degree or a fair number of friends in the scene would know what that is. I haven't seen it.

I guess there are two sorts of name-dropping. The first is the kind that Gibson and Sterling ostensibly employ, which is not only a requisite for historical accuracy but also probably inspired by their readings of historical documents from the time. I'm not really passionate about history*, but I can understand a writer finding certain people or projects worth incorporating into his work, especially if it happens with a bit of charicature, or a chance to give those people or projects a space in which to slide out from obscurity and finally get some acclaim. The second type of name-dropping is gratuitous, empty of real investigation. I find this mention of I Am Curious (Yellow) by Lethem to have this ring - he needed an obscure film, one likely to be released by Criterion, that could make for an interesting line or two (a chance to mention "bare bodies of hippies cavorting in a mud puddle"). Fair enough, I guess, if you're just trying to fill in a setting - and it never hurts to learn new things. But if anyone ran straight to Youtube for clips of Yellow, they'd be wasting their time as far as the novel goes. It seems a requirement that people keep one eye on Google throughout the reading of The Difference Engine. The famous difficulty of reading it in the early '90s was that these resources weren't handy enough; people with prior knowledge had an inestimable advantage.

When you read fantasy, especially large series, you more often than not get a handy glossary of names and places at the end. The urge to create an entire universe comes with the knowledge that the reader might get lost at times. When you recreate a time, however factual, that not many people would know about by chance (in comparison to, say, any book written about World War II), the same sort of rule should apply. The Difference Dictionary was created precisely to address this failing. I can't say yet whether The Difference Engine's references are always relevant to the book and never gratuitous, or if I'll feel like I wasted my time learning all these new names. The difference may just lay in the power of the authors to convince me that the characters deserve to be read about.

- Allana

*I apologize for the generality of this statement, and want to point out that it means my personal interest in name-dropping is exclusively for cohesion within the book, not necessarily a wider importance to the world at large. If you're the type that's always hungry for new knowledge and won't let a single reference slip by without devouring all relevant material, then all name-dropping is probably quite enjoyable for you.

Written by Allana on Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Known Issues, part two.

I feel sort of silly addressing this concern. I mean, who honestly complains that a story "doesn't really go anywhere?"

The defense of The Difference Engine seems easily summed up by the number of positive reviews shutting these complaints down with "The plotlines were clearly seen through in the third portion." So I'm not even going to bother dealing with it. What surprises me here is that readers still insist on that sort of closure in books, generally. Granted, it takes all kinds, but this insistence on "tying up loose ends" is usually code for "why isn't there a happy ending?" Things as straightforward as "He never saw Molly again" wouldn't be the kind of summary these people would find satisfying. The beatniks (whose work I first read about the same time as Gibson, a decade ago) taught me that "endings" aren't really endings, just places where the narrative stops. Their books were full of ups and downs and amazing joys and deep sorrows, and that sort of emotional cycle isn't contained within the arc of a story but repeats itself endlessly throughout a lifetime. I could sprinkle this post with names of brilliant books with meandering plotlines and unhappy endings, but I'd hate to belabour the point. I'd rather purchase copies and deliver them to these reviewers, because the only conclusion I can make is that They Must Not Read Very Much. Not a crime, in and of itself, but sort of silly for one who undertakes to review books on a book website. (Don't even get me started on the spelling and grammar.)

And we're still talking about traditional narrative here -- a lot of these naysayers mention that the subplots in The Difference Engine are more like vignettes, glimpses into lives in progress painted in broad strokes. A vignette style can be one of the most powerful ones in use, if you know how to use it (the best example being Georges Perec's Life A User's Manual, which not only uses the tableau as a successful gimmick but pushes it to a career-defining grace). If the complaint is that these writers don't know how to use it, well, that's not really the same thing, is it?

It's just about enough to make me give up reading other people's reviews. The most important thing I learned from writing music criticism is that you have to let the readers in on a little bit about yourself - something small but telling, so they'll know right away whether they're aligned with or against you. It's the only way for them to know whether they want to obey or disobey your commands. Who the writer is is as important as what the writer writes. Again, it takes all kinds, but if the people writing these critiques are the kind of people who can't be satisfied with an unhappy ending or a non-fairy-tale, I can't see myself being anything other than overjoyed to embrace The Difference Engine. The enemy of my enemy is my friend.

- Allana

Written by Allana on Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Tit Tat Too

Hey! An unexpected data dump of Charles Babbage related links, thanks to Bruce Sterling's blog at Wired:

Charles Babbage speculates up a series of tubes!

Bruce Sterling reads through some descriptions of the proposed capabilities of the Analytical Engine and equates them to their current computing analogues:

Now it may happen in addition that two or more numbers being added together, there may not be room at the top of the column for the left hand figure of the result. This would usually happen from an oversight in preparing or arranging the cards when space should be left; but it might so happen that the calculation led, as mathematical problems sometimes do, through infinity. In either case a bell would be rung and the engine stopped (((bug)))

This principle of “Chain” is used also to govern the engine in those cases where the mathematician himself is not able to say beforehand what may happen, and what course is to be pursued, but has to let it depend on the intermediate result of the calculation arrived at. (((generative art))) He may wish to shape it in different ways according as one or several events may occur, and “Chain” gives him the power to do it mechanically. By this contrivance machines to play simple games of skill such as “tit tat too” have been designed. (((computer games)))

He then points out this great glossary explaining what components of the Analytical Engine equate to what components of a modern computer, which is one page of John Walker's great accumulation of historical documents about the Analytical Engine, some by Charles Babbage's son.

Quite a lot of background reading here to prepare for the novel!

- Bill

Written by Bill on Monday, March 29, 2010

Known Issues, part one.

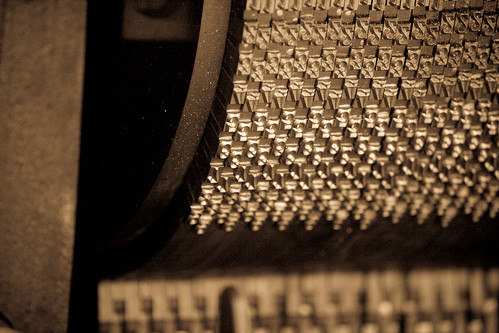

Photo from LexMachina's Flickr photostream.

Sometimes I can reverse-psychologize myself into liking things. The best way to work this trick is to play on my natural tendency to be a devil's advocate, to root for the underdog. Reading reviews makes me picture The Difference Engine as one such underdog. There are a few common complaints that are already making me raise eyebrows, and the theory is that, if I can point out how those expectations or confusions are unrealistic, I'll feel allied with the book before I even begin.

(Caveat: This might be highly unfair to the book, or myself, or the experience of reading in general. I'm still mulling over the moral implications.)

Often reviewers decry the glossing-over of the changes in technology that the entire plot springs from. This is where some history lessons are useful: Charles Babbage tried to design the first computer, a mechanical device that would perform advanced mathematical calculations. We're not talking "computers" here, no microchips or binary or circuit boards; this engine was operated by a hand crank. The original design failed, and government funding was withdrawn when the project became too expensive to support. An improved design, the Difference Engine No. 2, was used as reference material by rival inventors. A century and a half later, modern scientists were able to build a successful Difference Engine No. 2. Some "minor errors" were found in Babbage's schematics, but the machine was fully operational by the end.

So you see, I can't imagine this novel not glossing over the details of the technology. A world where Babbage's ideas worked is impossible. Impossible. It didn't work because he couldn't make it work and this is indicative of the state of his entire culture. In order to write about an alternative culture, truth needed to be discarded.

The point of a "historical reimagining" is that we're suspending our disbelief for a while and allowing ourselves to go along with an assumption. Sometimes we like to call these axioms: things that may or may not be true, but will lead to fun outcomes if we follow along with them. They're the basis of philosophy, of arguments, of fiction. I don't think I have to mention that Gibson and Sterling are writers, not scientists - their jobs are to predict and theorize about the way things affect daily life. I'm relatively mechanically inclined but I doubt I could summarize the difference engine's mathematical functions in layman's terms. And why should I have to?* Why should they have to spend more than a succinct paragraph or two describing how the machines work when the real story is in how people's lives change around them? Borges never had to explain how The Library or The Lottery really worked, because he was too busy telling us important, mind-blowing things about how society worked in those situations. And those stories are the best in the world.

- Allana

*Of course, I'll probably try at some point, because why not?

Written by Allana on Monday, March 29, 2010

Steamplay

There are a couple of things you wrote that I want to get a bit further into, but to start with:

while I don't find much appeal in steampunk culture past its colour palette and the occasional whimsical machine that actually functions, I have no issue with historical reimaginings

I think I'm with you there. I don't see steampunk as cohesive other than as sort of a fantasy-enhanced Victoriana. It seems to be centered around dressing up for conventions or other pop/alt cultural events. There's a whole topic of conversation in itself - the way that costumed clans have grown into whole social scenes within the Comics/SF&F Convention world. It has a kinship to the Goth scene, but is less club-going and more about conventions. The style is more costume than clothing. I guess I think of Goth as a fashion/mindset and Steampunk as a pose, or a kind of play.

There is also a connection to the contemporary maker scene, with custom clothing and jewelry making as major focuses of activity. Search "Steampunk" on Etsy and you'll have plenty to look at. There are the occasional clever devices that actually function in some way, as you mention, but mostly it's just cobbled together brass, wood and gears to give a mechanical feel. In some ways I find it depressing; a large amount of effort is put into assembling broken junk into non-functional meta-junk.

Steampunk is people like the League of Steam who mainly build imaginary ghost-hunting devices and maintain a kind of ongoing performance art existence as characters from an imaginary past. But then look at the the people at the Science Museum in London who built an actual, functioning Babbage Engine*. Most of us wouldn't call them "steampunk" as they don't play in the aesthetic, but what they've built is an honest, functioning steam era mechanical computer. They essentially made an alternate-history science fictional device that actually works.

I guess I shouldn't discount the value of the aesthetic as play. Science Fiction as a literary genre itself is a codified form of make-believe. But I think there is a continuum of play here, with ideas at one pole and aesthetics at the other. Today steampunk has drifted pretty far toward the latter, and I'd like it better, I think, if it were closer to the former.

- Bill

*Allana has a post that deals with the Babbage Engine coming up, so I kind of stole some thunder here... sorry! I just needed it to draw a proper contrast. I will try not to do that again!

Written by Bill on Sunday, March 28, 2010

Fail again. Fail better.

I'm the sort that wants to read a book in a vacuum, straight through, without doing research or checking out reviews. I don't even like reading jackets or excerpts, because my brain too easily remembers those hints of plot points to come; I find having an idea of what's coming makes me more impatient with what's in front of me.

But I've been afraid of The Difference Engine for almost a decade, and my normal approach seems to be useless here. It was handed to me by my father, a sci-fi and western fan; I couldn't get past the first chapter. From what I remember, I was put off by the dialogue, and wasn't having an easy time figuring out the setting. I had read at least a few Gibsons by that time, definitely Virtual Light and Count Zero. But I had never heard of Bruce Sterling, and blamed him for the difficulty and obtuseness.

Now, a decade later, I've become less enchanted by Gibson's work; All Tomorrow's Parties and Spook Country were more like indulgences of nostalgia for me. While Sterling's fiction leaves me underwhelmed, I'm enamoured with his essays and ideas, especially his yearly "State Of The World" online discussions. And, while I don't find much appeal in steampunk culture past its colour palette and the occasional whimsical machine that actually functions, I have no issue with historical reimaginings as opposed to futuristic fantasies.

I am, however, giving myself a bit of leeway: I'm allowing myself all the virtual assistance I feel I require, from help with the historical references to interpretations from other readers. Of course, my esteemed colleague Bill will be here to assist/guide/berate me as needed (I only hope I can return the favour). If, God forbid, I still can't manage to claw my way through this book, I'll have nothing to blame but my own fool stubbornness.

It's important to note, I think, that Bill and I are both coming at this specific book from the same angle, though our reading histories and personal preferences are quite diverse. That either says something about The Difference Engine or about the people who read it. If it's as obtuse as it's famed to be, maybe our separate backgrounds will lead us off on unique paths of speculation. The only thing I fear in this exercise is that we'll both fail, again, and pronounce it a flop in unison. Still, at least we'd have an answer.

- Allana

Written by Allana on Sunday, March 28, 2010

Completely lost in a bad way...

This picture of part of the difference engine's printer linked to from brianjmatis' Flickr photostream, he owns the picture; made available under a creative commons license, some rights reserved.

I've had an on/off love of Bruce Sterling's fiction. I love all his non-fiction and I love hearing his talks. I find him to be a huge intellectual inspiration, and I also find his emotional engagement with design to be moving and genuine. I'm predisposed to appreciate the unique quirks of his style, which I think probably makes up for a lot.

That said, I got completely lost in a bad way inside The Difference Engine. I still have no idea what actually happened in that book.

This novel is the ancestor of the Steampunk aesthetic, but as far as I can tell sits back there at the bottom of it all, forgotten and unloved. Victorian flavored technopunk art has spread out omnivorously through a garden of influences, these days taking a much more absurdist, fantastical stance than Sterling and Gibson's solidly engineered extrapolation. Steampunk aestheticians are more likely to point to Jules Verne or HG Wells as influences, and engage in vampire hunting and ectoplasmic misadventures.

But the subgenre was founded on cryptography and pressure driven gears.

So a couple of months ago in a discussion I was talking up the virtues of Sterling's book The Caryatids and managed through sheer force of my mighty rhetoric to drive Allana to the library, an expedition from which she returned disappointed. In the conversation that followed about aspects of Bruce Sterling's fiction that do or don't work for us, we ended up sort of challenging each other to a public re-read of what I think of as his most unreadable novel. This is the result.

We'll get going on the reading in a couple of days, and conduct an ongoing dialog/argument here as we go. We'll try throwing in some background, history, perspective based on the time it was written (1990), and how it reads in a contemporary context.

I hope to finally figure out what actually occurs in it, and maybe even remember a character or two this time!

(Spoken with affection - as I love most of the work of both Sterling and Gibson. This book remains their problem child. I'm willing to give it the chance of proving itself a misunderstood prodigy after a second, careful read.)

So - over to you, Allana; say hello to the people, and tell us what you're up to here!

- Bill

Written by Bill on Sunday, March 28, 2010